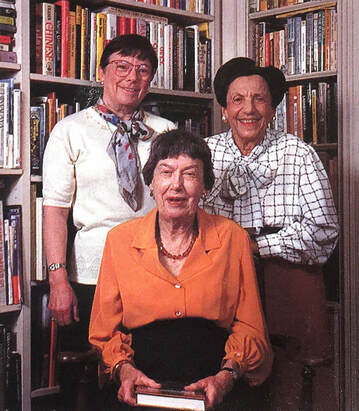

From left to right, Margaret Mayer, Mary Loise Stong, and Marjorie Stern, photographed in 1995.

Historical data cited from and photo credited to A Free Library in the City, by Peter Booth Wiley.

From left to right, Margaret Mayer, Mary Loise Stong, and Marjorie Stern, photographed in 1995.

Historical data cited from and photo credited to A Free Library in the City, by Peter Booth Wiley.

|

The Making of the San Francisco Library Movement

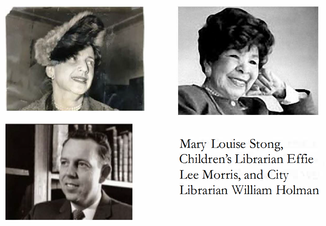

Chapter 3: Civil Rights, a Literary Renaissance - and still no new Main Library Defeated in his attempt to build a new Main Library, Librarian Holman drew on the civil rights activism pulsating on the streets in the late 1960s and took the library directly to the people. Librarians went door-to-door, familiarizing residents with library services in English, Spanish, Chinese, and Tagalog, visited community centers and housing projects, and even distributed free books on the street. Effie Lee Morris sent the first bookmobile to the Bayview. Simultaneously, community rooms were added to the Chinatown Branch, and Friends raised money for collections and a bibliographic study of African-Americans in the West. The SFPL also received federal funding from the Economic Opportunity Act for its fledging Jobs and Careers program for the unemployed. |

In 1975 city librarian Kevin Starr marched the library budget across Civic Center plaza to City Hall, accompanied by a band from San Francisco Conservatory of music dressed as ragged and bloodied Minutemen.

|

ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICES &

|

Get INvolvedContact UsTax ID Number: 94-6085452 ©2021 Friends of the San Francisco Public Library

|

SUBSCRIBE TODAY FOR UPDATES!

|